YAMAHA

XS650B

Line

Leadership At Yamaha Belongs To The 650 . . . A Tall Order For A Vertical Twin

Original

article appeared in Cycle World magazine December, 1974 issue

When

other manufacturers are dazzling the motorcycle world with innovative new

models and displays of R&D genius in their

top-of-the-line equipment, Yamaha seems content to rest on its laurels...or

at least on the steadfast solidarity and age-old appeal of the 650 Vertical

Twin. Displacing the never-weaned

750 Twin from the head of the Yamaha pack, the OHC 650 goes up against stiff

competition with practical, but non-earthshaking credentials.

When

other manufacturers are dazzling the motorcycle world with innovative new

models and displays of R&D genius in their

top-of-the-line equipment, Yamaha seems content to rest on its laurels...or

at least on the steadfast solidarity and age-old appeal of the 650 Vertical

Twin. Displacing the never-weaned

750 Twin from the head of the Yamaha pack, the OHC 650 goes up against stiff

competition with practical, but non-earthshaking credentials.

It’s the traditional British concept in a far more

refined and civilized, yet still incomplete package, despite six years of

fussing. That’s what we said...six years.

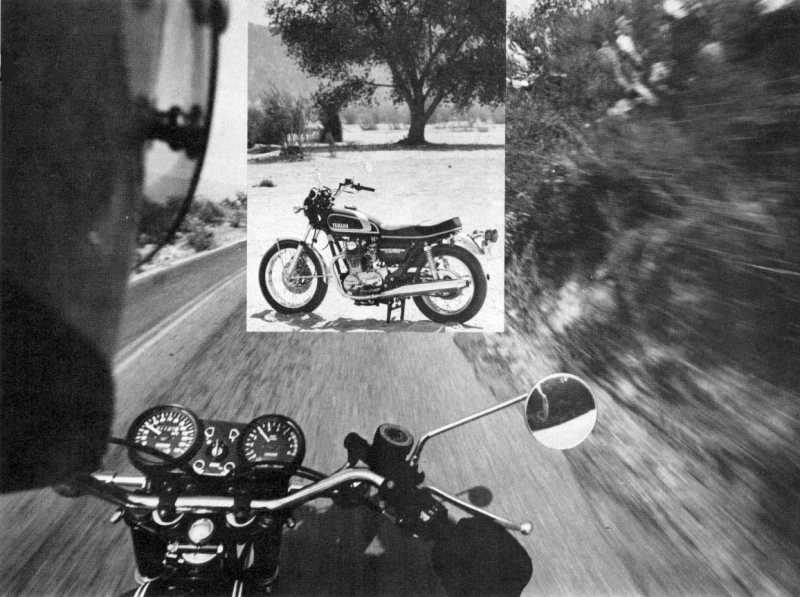

Seems almost like yesterday that the 1970 green and white, XS1 was

introduced; the bike with the right idea but a long way to go.

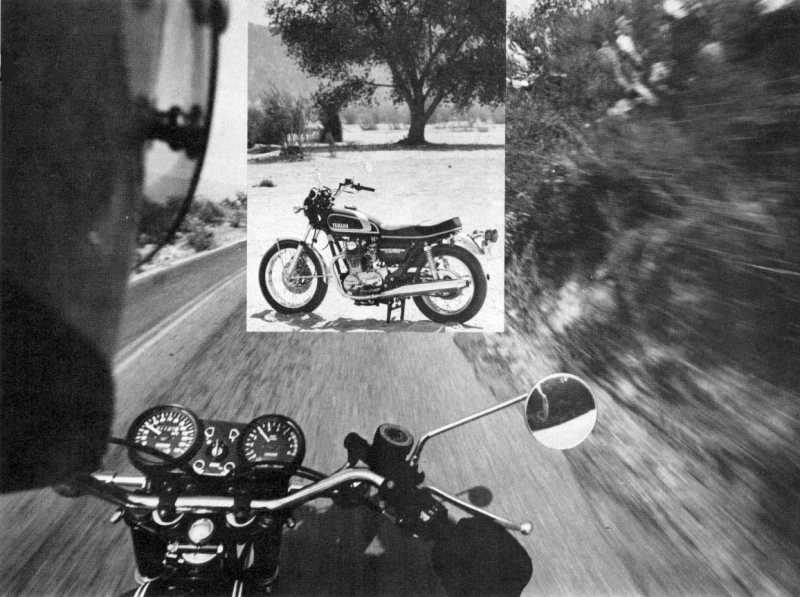

And it’s gone a long way; on to the XS1B, the XS2, the TX650 and

TX650A...to now, the XS650B. But there’s been a whole lot more going down than

mere alphabet changes. One ride gives more than subtle indication that the XS650B is

a vastly improved and different motorcycle than the original XS1.

But even the original was lauded as the Twin to end

traditional British woes. No

more oil leaks they said. No more

electrical problems they promised. Quieter was the word.

“Numbing vibrations cut drastically,” read the bold type.

And even the promise of push-button starting.

Hark! A Beezer-Trump minus the acne.

But it was not to be.

Though

the XSl followed through and delivered many of those expected promises, it

lacked an all-important ingredient, the type you cannot put your finger on.

Distress came to many when they found that the XS1 felt Japanese.

So what’s wrong with a Japanese motorcycle feeling Japanese?

Everything...when it’s supposed to feel British.

After

years of Triumph and BSA Twins, riders were ingrained with the idea that

the Britains had themselves a couple of motorcycles that handled beautifully.

That they did. For many

riders that feature alone (coupled with good engine performance), outweighed the

hassles then inherent in a British piece of equipment.

Conversely, all the goodies and conveniences found on Yamaha’s new 650 did

not outweigh the fact that it steered like a wheelbarrow and could be

downright treacherous in certain situations. So in the period of time from then

to now, Yamaha has gone to work on its 650 to correct the imperfections, while

the British have teetered on the edge of doom, beset with labor problems. Yamaha

has succeeded in clearing up many of its; the British are still struggling.

The

XS2B (TX650) of 1973 is virtually a carbon copy of last year’s TX650A…with

some new paint. Significant changes

had taken place in the ‘73/‘74 models and Yamaha was apparently satisfied

with the results, hence the lack of giant upheavals in the present model.

Smoothness

is now a touted feature of many machines in the industry.

Yamaha felt the trait important enough to warrant complex contra rotating

weights and balancers in their 500 and 750 Twins.

The 500 has been successful, the 750 not.

And in the meantime, Yamaha was bugged with a 650 that shook...more than

noticeably. So with all this

emphasis on smoothness and consumer awareness (from reading motorcycle

magazines), they went to work on the problem in the simplest terms possible.

This meant curing what they had, thus not entailing a major redesign or

engineering blast.

Compression

ratios were lowered, then raised. Nothing

too significant happened. Pistons were then lightened 20 percent to reduce the

reciprocating mass inside the engine. Add to this lighter connecting rods, and things start falling

into place. The 650 was smoother.

Most

motorcycle enthusiasts realize that this 650 vertical Twin is much more than

just another engine to Yamaha. It

was and is their legal connection to AMA professional dirt track racing, their

basis for the power unit in the machines run by National Champ Ken Roberts, who

twice has given Yamaha that Number One plate.

And that single digit number is worth much in terms of sales, not just of

650s but of everything in the Yamaha line-up. Number One means exposure and plenty of free advertising.

And this is the motor that got them there, though the differences in

Roberts’ engine and the unit in a standard XS2B are equatable to those between

an armadillo and a tiger.

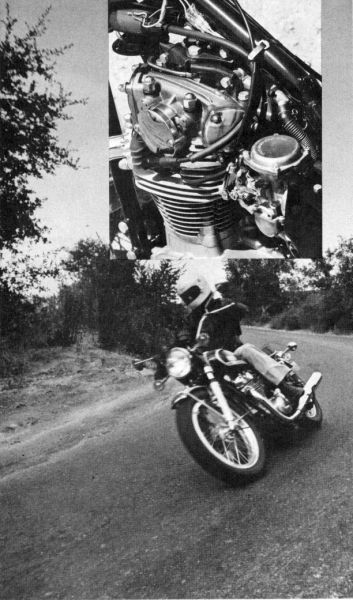

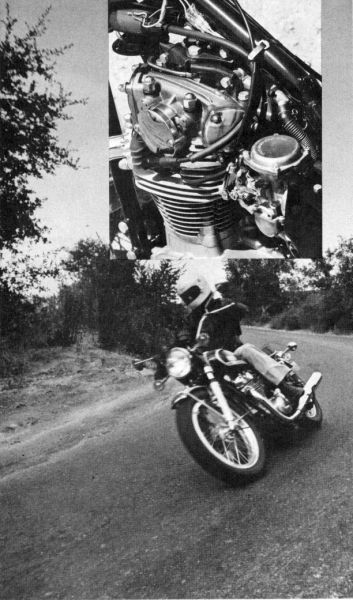

Like

a British Twin, the engine is compact, simple and straight forward.

Unlike older Triumphs and BSAs, oil leaks are minimal, but the latest

Triumphs are much better in that respect as well, so that advantage is of lesser

significance. There are no pushrods

to operate the valves, rather a simpler and more efficient single overhead

camshaft. The cam gets its drive

from a single-row chain running from the center of the crankshaft.

Chain tension is maintained by an idler gear located behind the cylinder.

Professional

racers switching from Triumphs to Yamahas often have problems getting used to

the Yamaha’s quick to rev-and-unrev type of power delivery.

Gene Romero, factory team rider, relates the feeling back to 1965 and his

Triumphs. “You gotta keep ‘em

revving off the corners or they’ll bog just like the old 500s.

This is due to the small size of the Yamaha flywheels, and this quick

revving ability is immediately apparent in the stock machine as well as the

racing equipment, Sitting at standstill and blipping the throttle gets an

immediate reaction from the engine. And

the lack of flywheel effect lets the rider know in an instant if he has selected

too high a gear in a particular situation.

The 650 will buck and stumble until the rider gets wise.

Common

practice on many bikes is a pressed-together crankshaft assembly, and the 650

Yamaha follows suit. Four

full-circle crank wheels are employed and the center shaft and wheels are

splined to prevent the movement or variance of these parts. Three roller bearings and a ball bearing support the crank

assembly. Few problems have ever

beset this area so we know they’re robust enough.

The lighter connecting rods turn on needle bearings.

A 360-degree crank configuration means that the pistons travel up and

down together; the rump, rump, rump of the exhaust gives that away in an

instant.

Common

practice on many bikes is a pressed-together crankshaft assembly, and the 650

Yamaha follows suit. Four

full-circle crank wheels are employed and the center shaft and wheels are

splined to prevent the movement or variance of these parts. Three roller bearings and a ball bearing support the crank

assembly. Few problems have ever

beset this area so we know they’re robust enough.

The lighter connecting rods turn on needle bearings.

A 360-degree crank configuration means that the pistons travel up and

down together; the rump, rump, rump of the exhaust gives that away in an

instant.

Straight

cut gears hook up the crank and mainshaft of the five-speed transmission.

Straight-cut gears are noisy but efficient, neither of which is apparent

to the rider of the 650.

A

medium to hard tug on the clutch handle operates the five metal and six

cork-lined friction plates of the wet clutch assembly.

Six springs provide the tension to hold the plates in position.

The clutch hub bushing is lubricated by pressurized oil from the

main shaft.

Shifting

our particular test machine was a bit peculiar. It seemed as though the rider had to force the gears into

position; not that it caused missed shifts or problems such as that...it was

just disconcerting to put so much pressure on the gear-change lever.

Lever travel, by the way, is short.

Coupled with the boot pressure necessary for clean shifts, it made the

gearbox feel vague. At times

neutral was evasive as well. Much

of the time we resorted to finding the “N” quadrant when rolling to a stop.

Far easier that way. Ratios

are well matched to the engine and allow good acceleration as well as sufficient

top speed.

The

recommended 20/50-wt. engine oil is delivered by a trochoidal pump (rotary type)

to the main bearings, crank pins, transmission main shaft, clutch bushing,

shifter fork guide bar and rocker arms. The remainder of the engine parts are lubricated by “oil

splash.” A convenient dipstick

lets the rider keep tabs on oil level.

Conventional

and usually reliable battery ignition is used on the 650.

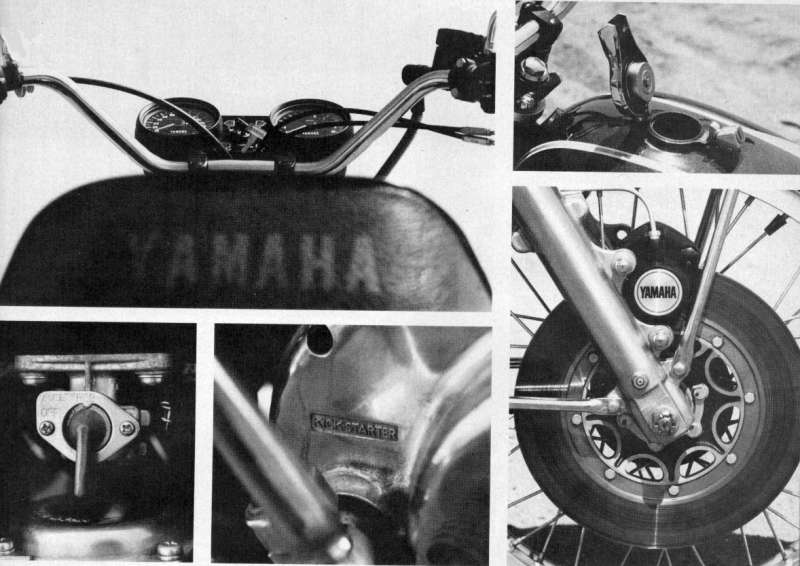

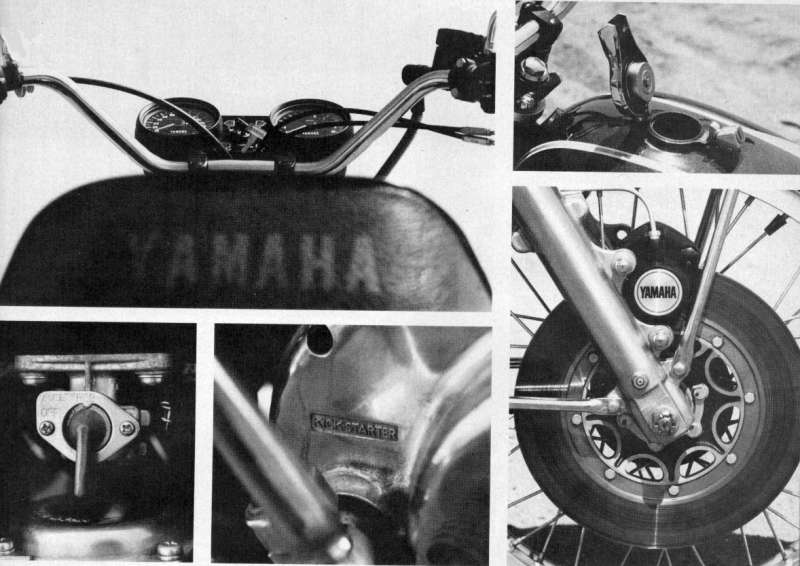

Two sets of points, located on the upper left of the cylinder head,

trigger the secondary coils at the prescribed time and furnish spark for the

plugs. The points are fitted

directly to the camshaft. An

advance mechanism is used to retard the timing for easy starting and smooth

idle. Yamaha dropped the previously

used compression release from the 650 when they discovered that it wasn’t

necessary to allow the hefty starter motor to spin the engine over.

Works just fine, without it, thanks.

Part

of the reason for a smoother running Yamaha 650 is the carburetion.

The twin 38mm Mikunis are of the constant velocity type, similar to those

fitted on the 500 Twin. Uneven

transitions in carb operation have been eliminated by changes in metering and

circuitry.

Constant

velocity carburetion is interesting. The

velocity of the fuel mixture through the venturi, regulated by the opening of

the butterfly and engine speed, causes a pressure difference between the top and

bottom of the carb piston. The

pressure difference raises and lowers the piston.

If the throttle were snapped closed, the piston would have a tendency to

float in the bore of the carb until the pressure was stabilized.

The diaphragm tends to dampen this movement and eliminates the

accompanying surge. Performance and

operating economy gain as a result. We

averaged 47 mpg in many different types of riding, none of which included

“babying” the motorcycle. With

the four-gal. fuel tank, effective range with reserve approaches 200 miles.

Generally our XS went on reserve at about 160 to 165 miles on the

resettable odometer. Roughly seven-tenths of a gallon would remain at this

point.

Like

we have said, the latest 650 Yamaha is decidedly smoother than its predecessors.

The numbing vibration of the past is gone.

But the bike is still not comfortable enough for longer trips.

Even though the handlebars are rubber-mounted, their shape sits the rider

straight up on the seat and in the force of the wind.

A slightly lower and more forward position would lean the rider into the

wind and into a far more comfortable proposition.

Grips are far too hard, and all but eliminate the advantage of the

rubber-mounted bars. And the

seat...typically Japanese, is good for about 100 miles of highway before the

rider starts looking for a massage parlor to get the circulation going again in

his butt.

The

current 650 is blessed with the same frame geometry as past versions but heavier

gusseting, stronger tubing and a longer swinging arm add much to handling.

Yokohama tires are new too, and though not nearly the best, they do a far

better job than what came as original equipment before.

Most of the new gusseting is concentrated at the steering head and in the

swinging arm pivot locations. Reduced

flex in all areas is readily apparent. Safer,

better...yes, but still not a Triumph or a bike that one will want to throw

around casually on twisty roads. It

does not have the tires or the ground clearance or the heritage of the RD350.

And the suspension lacks heavily in many important respects.

The

current 650 is blessed with the same frame geometry as past versions but heavier

gusseting, stronger tubing and a longer swinging arm add much to handling.

Yokohama tires are new too, and though not nearly the best, they do a far

better job than what came as original equipment before.

Most of the new gusseting is concentrated at the steering head and in the

swinging arm pivot locations. Reduced

flex in all areas is readily apparent. Safer,

better...yes, but still not a Triumph or a bike that one will want to throw

around casually on twisty roads. It

does not have the tires or the ground clearance or the heritage of the RD350.

And the suspension lacks heavily in many important respects.

Rough

surfaces bounce the machine around to the point of grip-tightening concern,

especially when leaned over in a bend. Front

forks remain oblivious to many surface irregularities; the ones that get their

attention usually get the rider’s too as he steers around them.

The rear shocks feel at times as

though

they were made

from bar stock; they’re

that

indifferent to the bumps. So

the 650’s suspension is the

next

area Yamaha’s engineers should turn their attention

to. As it stands, accessory shocks

are in order for any type of riding and the forks will have to be diddled with.

If not, a kidney belt is in order.

Much

of the remainder of the machine is typically Yamaha; finish is good but

overdone, brakes work better than “good,” even though the tires can’t keep

up, warning lights do lots warning. A

good deal of Yamaha tradition remains.

But

it’s what doesn’t

remain that’s important. Yamaha’s 650 is a better motorcycle.

In this day and age of Threes, Fours, Sixes, even Rotarys, what can be

said for the likes of a 650 vertical Twin? Plenty. And we’re glad it’s

here....

When

other manufacturers are dazzling the motorcycle world with innovative new

models and displays of R&D genius in their

top-of-the-line equipment, Yamaha seems content to rest on its laurels...or

at least on the steadfast solidarity and age-old appeal of the 650 Vertical

Twin. Displacing the never-weaned

750 Twin from the head of the Yamaha pack, the OHC 650 goes up against stiff

competition with practical, but non-earthshaking credentials.

When

other manufacturers are dazzling the motorcycle world with innovative new

models and displays of R&D genius in their

top-of-the-line equipment, Yamaha seems content to rest on its laurels...or

at least on the steadfast solidarity and age-old appeal of the 650 Vertical

Twin. Displacing the never-weaned

750 Twin from the head of the Yamaha pack, the OHC 650 goes up against stiff

competition with practical, but non-earthshaking credentials.